Introduction

In this article…

An unformatted text document

Bear with me for a few seconds and take a look at this scan of a page of text I typed on a vintage typewriter.

This document has a single flow of text with no formatting. I think we could all agree that this is unstructured text. Presented in this way, this document is obviously not easy to read and understand.

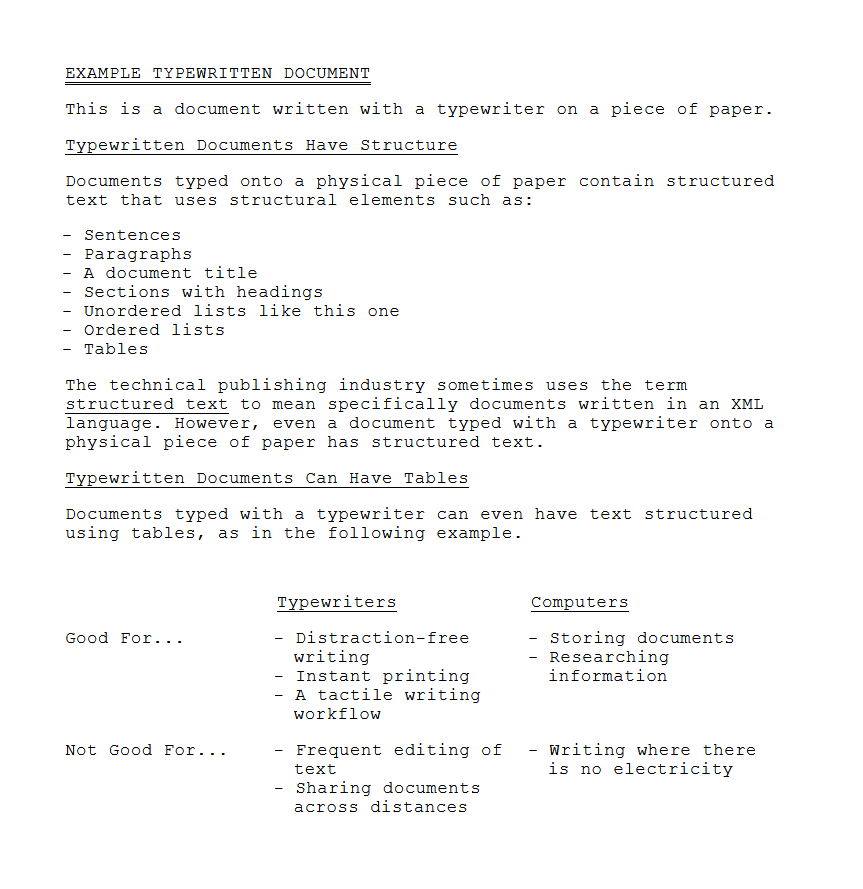

A simple formatted text document

Here are the same words re-typed on a typewriter, but this time I added some formatting.

To format this document, I used universally understood conventions for organizing text on a page to improve reading comprehension. I think we could agree that this is now a formatted document and that the text has structure (using a dictionary definition of "An arrangement and organization of interrelated elements"). This formatted, typewritten document is nothing more than words and punctuation characters printed in ink on a physical piece of paper (plus whitespace to separate the words for clarity). What You See Is All There Is (WYSIATI).

It’s worth noting at this point that although the text has structure, some writers would not call this a structured document because they reserve that term for something specific, as I’ll discuss later.

A digital plaintext document

The following screenshot shows the same text, but this time it is typed on a computer into the Notepad++ text editor using the plaintext (.txt) format.

It’s not identical because ASCII text doesn’t include an underline character equivalent to the underline key of a typewriter, but with the monospaced Courier font I chose, it’s close.

While text typed onto paper with a typewriter is easily scanned with optical character recognition (OCR) to digitize it, which is what I did for the first two examples above, this is not a realistic workflow for businesses. And, not to mention that typewriters are LOUD and for that reason alone they are not welcome in a modern office where even a clicky mechanical keyboard would cause a stir.

This plaintext document is the most basic kind of document we can create in a modern digital writing workflow.

A document structured with DITA XML

In this next example, I typed the same text typed into a text editor on a computer but this type coded it in the DITA XML language.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE concept PUBLIC "-//OASIS//DTD DITA Concept//EN" "concept.dtd">

<concept id="abcd">

<conbody>

<title>EXAMPLE TYPEWRITTEN DOCUMENT</title>

<p>This is a document written with a typewriter on a piece of paper.</p>

<section>

<title>Typewritten Documents Have Structure</title>

<p>Documents typed onto a physical piece of paper contain structured text that uses structural elements such as:</p>

<ul>

<li>Sentences</li>

<li>Paragraphs</li>

<li>A document title</li>

<li>Sections with headings</li>

<li>Unordered lists like this one</li>

<li>Ordered lists</li>

<li>Tables</li>

</ul>

<p>

The technical publishing industry sometimes uses the term <em>structured</em> text to mean specifically documents written in an XML language.

However, even a document typed with a typewriter onto a physical piece of paper has structured text.</p>

</section>

<section>

<title>Typewritten Documents Can Have Tables</title>

<p>Documents typed with a ty pewriter can even have text structured using tables, as in the following example.</p>

<table>

<tgroup cols="3">

<colspec colname="COLSPEC0" colwidth="1*"/>

<colspec colname="COLSPEC1" colwidth="1*"/>

<colspec colname="COLSPEC1" colwidth="1*"/>

<thead>

<row>

<entry colname="COLSPEC0" valign="top"></entry>

<entry colname="COLSPEC1" valign="top">Typewriters</entry>

<entry colname="COLSPEC1" valign="top">Computers</entry>

</row>

</thead>

<tbody>

<row>

<entry>Good For...</entry>

<entry>

<li>Distraction-free writing</li>

<li>Instant printing</li>

<li>A tactile writing workflow</li>

</entry>

<entry>

<li>Storing documents</li>

<li>Researching information</li>

</entry>

</row>

<row>

<entry>Not Good For...</entry>

<entry>

<li>Frequent editing of text</li>

<li>Sharing documents across distances</li>

</entry>

<entry>

<li>Writing where there is no electricity</li>

</entry>

</row>

</tbody>

</tgroup>

</table>

</section>

</conbody>

</concept>This text definitely has structure and is what many writers would call a structured document.

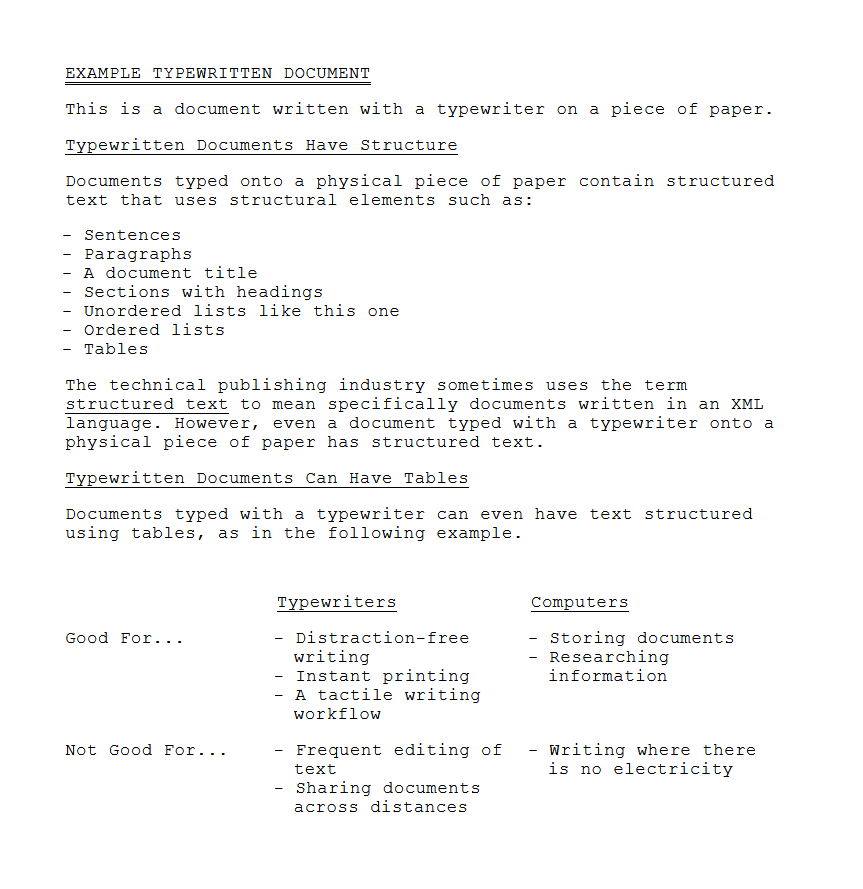

To use the DITA XML language, I had to add an extreme amount of markup to structure the document so it follows the rules of the language. What you see above, of course, is not what a reader of the document would see. It is the source code that the writer creates. To make the document look the way a reader may see it, I linked a Cascading Style Sheet (CSS) and opened the document in a browser. The result is shown in the following screenshot.

The rendered DITA document is identical to the typewritten page in content and structure. It is also very close to the typewritten page in its styling. Here are the two side-by-side, with the typewritten page on the left.

This comparison begs the question: How did we go from such a simple old-fashioned typewritten document to such a complex modern DITA document that contains twice as many characters, when they look the same?

From the reader’s perspective, the simple document and the complex document are identical. From the writer’s perspective, the DITA document is slower and more difficult to create, and it takes significant training to do so. It also takes real money to add complexity. You can pick up a typewriter and a piece of paper for $50, but it takes maybe $500,000 for software licenses, maintanance agreements, consulting fees, training fees, specialist staff salaries, and staff training time to get a working DITA publishing system with a component content management system. That may seem like a flippant comparison, but it’s actually the truth. So, why do we go to all this trouble to tag our text in separate source files that we then have to convert into something readable?

We tag for formatting and logical structure

In the example typewritten document we saw standard formatting conventions used for headings a bulleted list, a table, and paragraphs. On a typewriter or in a plaintext computer document you don’t need markup. What you see is all there is (WYSIATI). You simply apply the formatting as you type the text.

In a word processor, such as Microsoft Word, or desktop publishing application, such as Adobe FrameMaker, the markup tagging is added behind the scenes as you^ apply styles or formats. The styling, which approximates a printed output is displayed in the document on the screen but the markup tagging that the software adds to the document is hidden. This is the essence of a WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) environment.

In a text-based writing system like lightweight markup languages and XML, the markup tags are visible in the file, but obviously not in the rendered publication. We now have the idea of a source file with markup that is separate from the rendered publication we give to the audience. In an AsciiDoc source file, to declare that a piece of text is intended to have the structure of a heading, paragraph, bulleted list item, and a warning that needs a yellow triangle icon, you would use the following markup:

== This is a level two heading

This is a paragraph

* This is a bulleted list item

WARNING: This is a warning.For the same result in DITA XML you would use the following markup:

<section>

<title>This is a level two heading,</title>

<p>This is a paragraph.</p>

<ul>

<li>This is a bulleted list item.</li>

</ul>

<note type="warning">This is a warning.</note>

</section>In the typewritten and plaintext documents the text has formatting but no markup. If when you add markup, we give a document superpowers in the form if a logical structure. Logical structure has nothing to do with the styling or the position of the text on the page. It defines the relationships among the different text structures on the page. When a source document is rendered to a publication it is merged with a pre-prepared template. The template and document markup determine the relationships among the text elements. For example, an HTML rendering might have the following nested logical structure.

html

body

article

title

p

ol

liIn this structure, the <li> element is nested inside the <ol> element. The ol element is the 'parent' and the li element is the 'child'. Similarly, the p and ol elements are siblings. This logical structure can now also be represented as a document tree such as this:

…

Adding a logical structure to a document does something important. It creates an addressing system where the text elements in the structure become objects that are machine readable. The text objects can be targeted by a computer software for different purposes such as:

-

Adding typographical styling

-

Adding interactive behaviors

-

Conversion to synthesized voice

-

Automatically writing computer-based summaries

I will look at each example in turn.

We tag text for typographical styling

While elaborate color typography has been used on printing presses for a long time, early technical manuals often used basic styling that was presumably easier and cheaper to produce. My guess is that they were typed on a typewriter and the typed pages were used to prepare lithography plates for printing. Here is an example of a service manual for a typewriter written in 1956.

Today’s readers expect more refined typography than this. Better typography can improve reading comprehension by emphasizing elements that show the document’s structure. It is also more attractive to look at, which encourages reading, and can reinforce a company’s branding.

When a document is market up to indicate its logical structure, the screen or print rendering process can read this markup and apply particular typeface sizes, colors, etc. that the document designer has prescribed. For example, the third bulleted list item in the first section of the document should be colored orange with a blue background. Here is the rule that creates this style.

Here is the result in the rendered document.

…

Adding interactive behavior In addition to styling based on the logical structure of a document, if the document is destined for HTML delivery the document tree can be used by JavaScript scripts that run in a web browser to add interactive behavior to the document. For example, if you click a 'Details' link next to a section heading, an extra section of text can drop down to give more details about the subject being discussed. Here are before and after screenshots showing this behavior.

This mechanism can similarly be used to add faceted browsing. Faceted browsing is commonly seen on online stores where you can filter a long list of items by categories such as men’s, women’s, and kids.

In the technical writing world you could use screen-reader-software-applications filter on audience category such as novice user, advanced user, and administrator. However, I have not ever seen this actually implemented. Supporting screen readers Screen reader software applications are used by blind people to navigate and read documents on a computer screen. They rely on the marked-up logical structure of a document to do this. I’ve never heard of a company that supports screen readers in its technical documentation, but if there are some it would be one more reason why we tag technical documentation.

We tag text to support computer-generated summaries

The logical structure of documents distributed as web pages can be used by software to generate a summary of the document, especially if the names of the element tags are semantic/ (reflect the content that they contain).

While this may be valuable from an historical, archival perspective, and maybe for other types of content, today’s technology products and their user manuals are generally short-lived so this ability probably has little value for the technical writing team. User manuals are provided with the product, which satisfies the customer need at the time.

The typewriter referenced in the 1956 typewriter manual earlier is still used today because they were from an era when products were built to last. I don’t think the medical devices work with will be used 65 years from now. Probably not even 20 years from now. By then there will likely be a better technology to replace them.

We tag for more specific addressing Sometimes the logical structure of the document doesn’t give us the specificity we need to target particular pieces of text.

In these cases, we need to tag the text with id’s or classes depending on the context.

As an example of such document markup, if we wanted the third bulleted list item in a particular document to have a lime green text, with CSS we could use section:nth-of-type(3) to target it.

However, if we now add a new list above it, the wrong list would have the lime bulleted list item.

Me can solve this problem by giving just the list of interest an id. In the AsciiDoc language this would look like this.

(#lime)

* List item one

* List item two

* List item threeIn DITA XML we would use an id attribute like this.

<ul id="lime">

<li>List item one</li>

<li>List item two</li>

<li> List item three</li>

</ul>As an id can only he used once in a document, if you plan to have more than one bulleted list in your document with lime text, you need to use a class instead. For AsciiDoc this would look like this.

(.lime)

In DITA you would use the outputclass attribute like this,

(ul outputclass="lime")In the same way, classes and id’s may be needed for JavaScript scripts to add interactivity to specific text elements in the document. The software used to render this document to an HTML page or PDF file reads the markup information and applies the intended typography to the publication.

We tag text for page layout

In addition to typographical styling, we mark up text to customize the position we want it to occupy on the page. Overall page layout, such as the widths of margins and content of headers and footers is defined in the templates used and not in the test elements typed into the file, But, where some elements should be rendered one way and others rendered another way, you need to do 'individualized tagging' to indicate this.

If some images in the document need to be left aligned and others centered, you can’t use a global instruction. For example, to center a specific image on the page in an AsciiDoc source file we might add a class attribute called 'centered' like this.

[.centered]

image::example.jpg[]For a DITA document we would use:

<image align="center" src="example.jpg" />Overall page layout, such as the widths of margins and content of headers and footers is defined in the templates that are used and not in the text typed into the file. But where some elements should be

We tag text for publishing instructions

As previously mentioned, with WYSIWYG word processors and desktop publishing applications such as Microsoft Word and Adobe FrameMaker, the printed output is a close fascimile of the view on the screen, ""or text-based publishing tools, however, that is not the case for a couple of reasons.

The first reason relates to how the rendered document is styled. If the application used for text-based publishing has a styled view on the screen it is most likely an approximation of the final output created with a built-in generic stylesheet just to give you a sense of the output styling, which may help you to compose the document. The application you are writing in doesn’t know what the designer intends the output to look like. The actual styling instructions are stored in files that are part of the backend publishing system. Such systems employ separation of styling from content. The file you are typing in contains only the content, the logical structure of the document, and the metadata not (markup). The real styling information i^applied by the publishing software until the rendering process.

The second reason relates to how the rendered document is assembled or 'built' by the publishing system. Text-based publishing toolchains usually have the ability to build documents from individual pieces at the time you are ready to render the publication. In the writing soft?;are application you work on individual pieces and don’t ever see the entire publication until it is built. The pieces that belong in the publication are defined in a separate file that acts like a table of contents.

As well as defining the publication’s table of contents, this file may use other metadata to assist with publication assembly. For example, the cover page for a PDF publication may be defined entirely by pieces of metadata / in concert with a layout template instead of existing as a file that the writer creates. This metadata might include the publication title, cover image filename, publication date, publication part number, and so on. In DITA this information is stored in a 'map' file, which may look in part like this:

…

For a website published from AsciiDoc files using the AsciiDoctor processor and Antora layout templates, metadata stored in a configuration file sets the title of the website. In addition to specifying the publication’s table of contents and any generated pages, tagging can also indicate pieces of a topic that should be left out of or in eluded in a particular publication. This is because a topic you are writing may be used in two different publications (or more), some of the text may be unique to one publication while other text may be unique to the other. The remainder of the text is common to both. Tags are used to indicate the conditional text that is unique to each output. In AsciiDoc, a conditional paragraph unique to the manual for the luxury version of a car (LX) is marked up like this.

…

In DITA XML it might look like this:

…

The processor includes this text in the manual for the LX version of the car and leaves it out of the manual for the standard EX version.

Conditional text can also be used to denote text that should only be used in a particular output format. For example, you may want to add a list of hypertext links for an HTML version but not a PDF version destined for commercial printing.

As well as using markup to show or hide pieces of text for different publications/ using the same source file, markup can be used to pull in pieces of text from completely different files. The markup gives the addresses of these external pieces of text. Using AsciiDoc as an example, to pull into your topic some text that lives in a separate file called 'add-me.adoc' you would write in your topic:

include:add-me.adoc()To do the equivalent in a DITA document, depending on how the text fits into the existing structure you might write:

(section conref="add-me.xml/topic-id/section-id"/)We tag text for translation

The products our companies make are often sold across the World. Following regulatory requirements,and sales and marketing preferences that means we may need to translate our documents. For publishing toolchains that store all files in a database, if the language code is not appended to the filename we will need to add a global language attribute to the file.

To indicate which files are in which language, for example a topic written about how to turn on the product may exist in 28 languages, all with the same filename. In the language of the topic is denoted as follows:

<note xml:lang="en-us">The software used by translation vendors may only show parts of text with the relevant target language attribute. For example, if a document that is primarily US English is to be distributed in Canada, it may need to have warnings translated into French Canadian. The warnings may need to be tagged in the following way:

(note type="warning" xml:lang="fr-ca")...(/note)Another reason for specifying the language is that the styling of the document may need to change with certain languages. For example, an English document may use the Arial font but when the document is translated into Arabic it may need to use the Al Bayan font. Also, things like hyphenation styling may need to be different for different languages.

We tag for search engines For technical documents that will be distributed over a website or other searchable medium, such as a CD-ROM, the document may reed to be optimized for retrieval by a search engine. All of the necessary information needed to do this must be included in the source document. This is typically done by adding metadata to the head area of the document that can be read by the search engine.

AsciiDoc example…

DITA example…

We tag text to guide writers and constrain structure for consistency

We tag test to comply with a logical structure that the publishing system designers have decided are needed. To recap, the first example of test written on paper using a typewriter is formatted as a single continuous string. In the second example, the text typed onto paper is formatted into commonly understood document structures, such as paragraphs, a bulleted list, and a table. In the third example, the same text is typed into a text editor to create an equivalent digital version. This document has no markup, but it does have basic structure. By adding markup as in the example AsciiDoc and DI^A examples provided throughout, a nested logical structure is created that makes the document machine-readable and allow a separation of document logic from styling as well as automated production tasks such as the assembly of a rendered document from component parts that can be shared among publications.

In addition to these practical reasons for tagging text, tagging can also be used to tell the writer how a document must be structured. A superior within the writer’s organization, such as an information architect or manager, has decided that for consistency this type of document must be structured "this way". When using writing tools such as Adobe FrameMaker, these constraints are communicated with a style guide or template description document that writers reference, With XML writing languages, these constraints are communicated by a Document Type Definition (DTD) file for the language, developed according to the desires of the company superior or, for canned languages like DITA and DocBook, developed by an external group.

This file is used by software to validate that a document written by a technical writer has a markup that accurately follows these constraints. Any deviation from this required markup produces an error that blocks the writer from rendering the document through the publishing system. The pre-boxed DITA XML language in particular include a lot of constraints. These constraints go far beyond those needed to style publications and ensure consistency. They are an attempt to enforce a particular writing philosophy that the DITA developers believe is the best way to structure documentation. In fairness, customization of the rules is possible, but is rarely done, perhaps because of the significant expense to do so.

This is not the place to discuss the merits, or not thereof, DITA. The point is that markup can be used to try to enforce a particular writing structure and philosophy on writers. It is always possible for writers to subvert the intended use of the DITA elements, but that doesn’t change the intent of the markup.

Conclusion

That was a long discussion because markup is used for so many reasons in technical publishing. I’m sure there are other miscellaneous reasons that I haven’t included also.

It should be noted that although little or no technical writing is done these days with typewriters, not so much technical writing uses XML languages, which use the most markup* The majority of technical writing id still done with word processors, desktop publishing application s and specialized help authoring tools that add markup behind the scenes*

In summary, writers add markup to their documents for:

-

Typographical styling

-

Page layout

-

document assembly instructions

-

To allow computer applications to manipulate text objects that result from tagging

-

To support search engines and automatic document summaries

-

To support screen readers To indicate languages for translation management To enforce consistency for improved reading comprehension and to support processing by computer software

-

To enforce a philosophy of how best to structure documents comments embedded in files

Comments